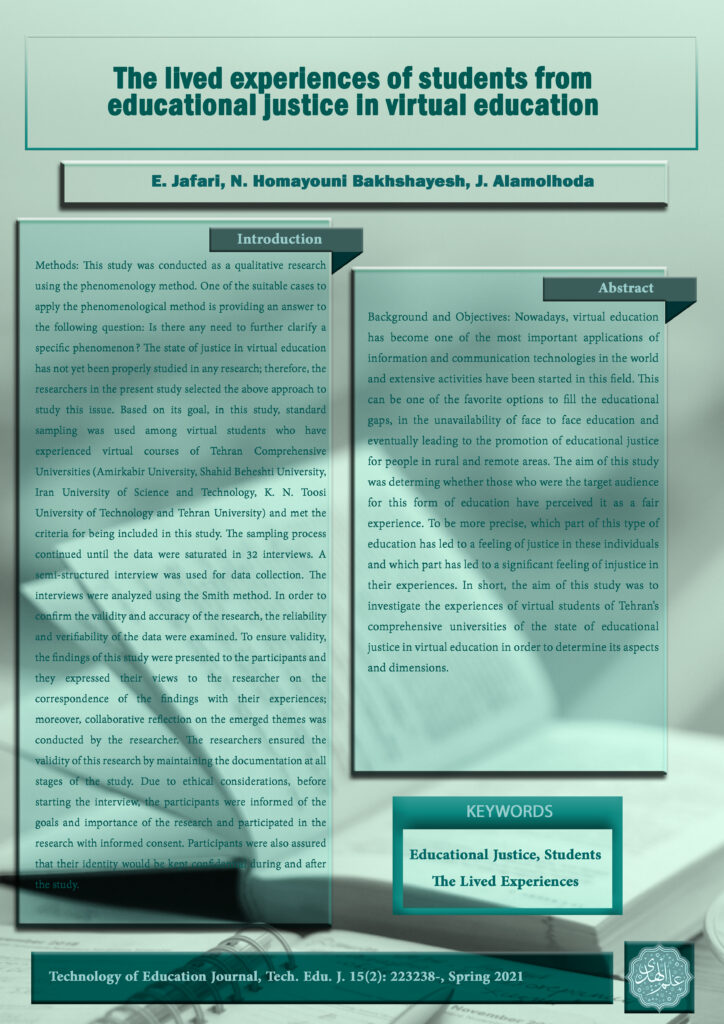

The lived experiences of students from educational justice in virtual education

Jafari*, 1, N. Homayouni Bakhshayesh 1, J. Alamolhoda2

1 Department of Higher Education, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran

2 Department of Educational leadership and development, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Shahid Beheshti

University, Tehran, Iran

ABSTRACT

Nowadays, virtual education has become one of the most important

applications of information and communication technologies in the world and extensive activities

have been started in this field. This can be one of the favorite options to fill the educational gaps,

in the unavailability of face to face education and eventually leading to the promotion of

educational justice for people in rural and remote areas. The aim of this study was determing

whether those who were the target audience for this form of education have perceived it as a fair

experience. To be more precise, which part of this type of education has led to a feeling of justice

in these individuals and which part has led to a significant feeling of injustice in their experiences.

In short, the aim of this study was to investigate the experiences of virtual students of Tehran’s

comprehensive universities of the state of educational justice in virtual education in order to

determine its aspects and dimensions.

Methods: This study was conducted as a qualitative research using the phenomenology method.

One of the suitable cases to apply the phenomenological method is providing an answer to the

following question: Is there any need to further clarify a specific phenomenon? The state of

justice in virtual education has not yet been properly studied in any research; therefore, the

researchers in the present study selected the above approach to study this issue. Based on its

goal, in this study, standard sampling was used among virtual students who have experienced

virtual courses of Tehran Comprehensive Universities (Amirkabir University, Shahid Beheshti

University, Iran University of Science and Technology, K. N. Toosi University of Technology and

Tehran University) and met the criteria for being included in this study. The sampling process

continued until the data were saturated in 32 interviews. A semi-structured interview was used

for data collection. The interviews were analyzed using the Smith method. In order to confirm the

validity and accuracy of the research, the reliability and verifiability of the data were examined.

To ensure validity, the findings of this study were presented to the participants and they

expressed their views to the researcher on the correspondence of the findings with their

experiences; moreover, collaborative reflection on the emerged themes was conducted by the

researcher. The researchers ensured the validity of this research by maintaining the

documentation at all stages of the study. Due to ethical considerations, before starting the

interview, the participants were informed of the goals and importance of the research and

participated in the research with informed consent. Participants were also assured that their

identity would be kept confidential during and after the study.

Findings: The main question of this research was: What experiences do students have regarding

justice and injustice in virtual education? In analyzing the interviews, the main concepts were

extracted from the sentences expressed by the participants and were represented in a reduced

conceptual form, resulting in 153 descriptive codes. In the next step, by reflecting on the

descriptive codes, overlapping, similar, and related codes were identified. These concepts were

integrated in the form of 20 interpretive codes based on commonalities, similarities and semantic

overlaps. Finally, in the last step, the interpretive codes were reduced to 7 explanatory codes:

students’ equity with different characteristics (geographical condition, job status, and learning

competence), students’ equality in their interaction with professors (equality despite differences

in appearance features and cultures), lack of real interactions (short and fragile interactions),

content problems (non-practical content, lack of supervision in content development and lack of

codified and specific planning in presenting courses), organizational misconceptions toward

virtual students (having capitalistic attitude to students and not paying attention to students’ real

abilities), inequality in the use of facilities and costs (high educational costs and inequality in the

use of facilities), and inequality in providing educational services (lack of appropriate

organizational behavior patterns suitable for virtual teaching, low staff number to meet the

educational needs of students, high number of students in classrooms and the use of

inappropriate teachers for teaching).

Conclusion: Justice and its realization has always been one of the main slogans in the field of

education. Participants in the present study have sometimes focused on communication and

sometimes focused on the facilities provided in the training process. If we take a general look at

the themes obtained, we can divide them into two spectrums of justice and injustice although

more examples have been found in the section on injustice. Another main conclusion that is drawn

from the present study is the predominant link between the instances of justice and the inherent

characteristics of virtual education and the predominant link between the instances of injustice

in the way the virtual teaching is managed and lack of facilities appropriate for this form of

education. Finally, it should be noted that due to the increasing use of virtual education and its

fundamental difference from face-to-face education, ethical issues also appear differently in its

process which require accurate recognition and study.

To download the full article file, click on the link below “The lived experiences of students from educational justice in virtual education”

Dr Jamilesadat Alamolhoda Personal Website

Dr Jamilesadat Alamolhoda Personal Website